Auteurs et autrices / Interview de Bryan Talbot (anglais)

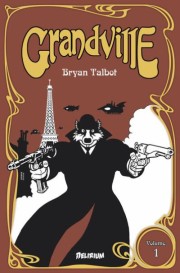

Bryan Talbot was a guest at the Angoulême 2024 festival, to mark the publication of “Grandville – Noël” in French with publisher Delirium... a great opportunity to meet "the father of British graphic novels" and chat about his books. (Read french version here.)

Voir toutes les séries de : Bryan Talbot

Hi Bryan, it’s very lovely to meet you. Have you been to Angoulême before?

Yes, it’s about my 12th time, I think. The first time I came was for the “British Year”, back in 1990. This was at the time when Angoulême used to have a country as a theme every year, and they’d invite a lot of people from that country. I was flown over with half of the British comic industry: Alan Moore, Pat Mills, 2000 AD, Grant Morrison, Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland. There was about 20 or 30 of us, flown to Bordeaux and then brought on a coach to Angoulême.

Could you please tell us how you got into drawing comics?

Well, I grew up with comics, drew them for my own amusement when I was a kid, even up to the age of about 14. But it never occurred to me that I would be able to make a living doing it when I grew up, I had no idea. All I knew was that the only things I was good at in school were English and art. I had no idea what I was going to do, but I knew it had something to do with art.

You are often referred to as the father of British graphic novels. What do think about that?

I think I’m in the running! (laughs) The first 3 graphic novels that came out around the same time were my “Luther Arkwright”, Raymond Briggs’s “When the wind blows” and Posy Simmonds’s “True Love”. But considering “Luther Arkwright” had been serialized 4 years before that, from 1978, I think I’ve got the edge! (laughs)

Posy Simmonds has just been awarded the “Grand Prix” in Angoulême.

Oh yes. She’s a friend of ours. In fact, the first time I met her was that year, that British year in Angoulême.

Hi Bryan, it’s very lovely to meet you. Have you been to Angoulême before?

Yes, it’s about my 12th time, I think. The first time I came was for the “British Year”, back in 1990. This was at the time when Angoulême used to have a country as a theme every year, and they’d invite a lot of people from that country. I was flown over with half of the British comic industry: Alan Moore, Pat Mills, 2000 AD, Grant Morrison, Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland. There was about 20 or 30 of us, flown to Bordeaux and then brought on a coach to Angoulême.

Could you please tell us how you got into drawing comics?

Well, I grew up with comics, drew them for my own amusement when I was a kid, even up to the age of about 14. But it never occurred to me that I would be able to make a living doing it when I grew up, I had no idea. All I knew was that the only things I was good at in school were English and art. I had no idea what I was going to do, but I knew it had something to do with art.

You are often referred to as the father of British graphic novels. What do think about that?

I think I’m in the running! (laughs) The first 3 graphic novels that came out around the same time were my “Luther Arkwright”, Raymond Briggs’s “When the wind blows” and Posy Simmonds’s “True Love”. But considering “Luther Arkwright” had been serialized 4 years before that, from 1978, I think I’ve got the edge! (laughs)

Posy Simmonds has just been awarded the “Grand Prix” in Angoulême.

Oh yes. She’s a friend of ours. In fact, the first time I met her was that year, that British year in Angoulême.

Grandville

Let’s focus on Grandville first, as it’s your current book coming out with your new French publisher Delirium. Could you please tell us what inspired you to write this steampunk story set in an alternative reality?

Usually, when I am working on a graphic novel, I get little ideas, bits and pieces, and I think about them, sometimes for years, before I actually do them. I accumulate ideas for scenes and characters and stuff like that. I make lots of notes, put them in a folder and keep them.

With Grandville it was the complete opposite. It all came in a complete rush. It arrived fully formed, it was incredible. One day, around 2006/7, I was clearing some books up in the studio, and I picked up a book on J.J. Grandville, aka Jean Ignace Isidore Gerard. I’d had this book for a couple of decades. And I just looked at the title, and I thought that Grandville could be a nickname for Paris in an alternative world where Paris is the biggest city in the world. Then I wondered “Well, why would it be the biggest city in the world?”, and I thought “Oh yeah, Napoleon won, and went on to conquer the world”, which was his plans. After Egypt, he planned to go off to India. He never got round to it, but in the world of Grandville, he did. And I started thinking about it, and it all came to me, over the week, while I was working on drawing something else. At the end of the week, I just sat down, and I typed it all out, the whole story.

Let’s focus on Grandville first, as it’s your current book coming out with your new French publisher Delirium. Could you please tell us what inspired you to write this steampunk story set in an alternative reality?

Usually, when I am working on a graphic novel, I get little ideas, bits and pieces, and I think about them, sometimes for years, before I actually do them. I accumulate ideas for scenes and characters and stuff like that. I make lots of notes, put them in a folder and keep them.

With Grandville it was the complete opposite. It all came in a complete rush. It arrived fully formed, it was incredible. One day, around 2006/7, I was clearing some books up in the studio, and I picked up a book on J.J. Grandville, aka Jean Ignace Isidore Gerard. I’d had this book for a couple of decades. And I just looked at the title, and I thought that Grandville could be a nickname for Paris in an alternative world where Paris is the biggest city in the world. Then I wondered “Well, why would it be the biggest city in the world?”, and I thought “Oh yeah, Napoleon won, and went on to conquer the world”, which was his plans. After Egypt, he planned to go off to India. He never got round to it, but in the world of Grandville, he did. And I started thinking about it, and it all came to me, over the week, while I was working on drawing something else. At the end of the week, I just sat down, and I typed it all out, the whole story.

And at what point did you decide it was going to be animals? Right from the start?

Well yeah, that was the idea, I got the idea from J.J. Grandville. I thought it should be a world populated by anthropomorphic animals. I had never done an anthropomorphic story before, I had been doing comics for 30 years at that point, and I had never done it. It was a challenge, something different.

So, after a week, I just sat down, started typing and wrote all the scenes out. Before that, every graphic novel I’d done, I’d actually worked out each page laboriously in thumbnails, and arranged them. In this case I didn’t, I could see each page, I just typed it out. The other Grandville books took a bit longer to develop.

From reading Grandville, I feel that you have a certain attachment to France. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, when I was about 5 or 6, I used to walk about a mile to the local library, and amazingly they had Tintin albums. They were in French, and I couldn’t read French, but I used to love them, I just followed the pictures. That was my first introduction to Franco-Belgian comics.

And at what point did you decide it was going to be animals? Right from the start?

Well yeah, that was the idea, I got the idea from J.J. Grandville. I thought it should be a world populated by anthropomorphic animals. I had never done an anthropomorphic story before, I had been doing comics for 30 years at that point, and I had never done it. It was a challenge, something different.

So, after a week, I just sat down, started typing and wrote all the scenes out. Before that, every graphic novel I’d done, I’d actually worked out each page laboriously in thumbnails, and arranged them. In this case I didn’t, I could see each page, I just typed it out. The other Grandville books took a bit longer to develop.

From reading Grandville, I feel that you have a certain attachment to France. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, when I was about 5 or 6, I used to walk about a mile to the local library, and amazingly they had Tintin albums. They were in French, and I couldn’t read French, but I used to love them, I just followed the pictures. That was my first introduction to Franco-Belgian comics.

In the 60s, a book came out in Britain called “The Penguin book of comics”. It was a formative book for me. It was the first time I saw anybody writing about the medium and treat it seriously. It wasn’t just a thing for kids, it was something that could be studied. And there was a section on European comics.

And then in the 70s, “Métal hurlant” started coming out. I saw it and it was a comic they made for me, you know. I used to get it every time I was in London - I’d pick up some copies from Forbidden Planet, or was it in Dark They Were and Golden Eyed. And through that, I started picking up “A suivre”, “Ah ! Nana” and other French comics. And at the end of the 70s I thought about learning French, because I couldn’t understand any of these comics, I was basically just buying them for the pictures and the storytelling, so I started learning French.

In the 60s, a book came out in Britain called “The Penguin book of comics”. It was a formative book for me. It was the first time I saw anybody writing about the medium and treat it seriously. It wasn’t just a thing for kids, it was something that could be studied. And there was a section on European comics.

And then in the 70s, “Métal hurlant” started coming out. I saw it and it was a comic they made for me, you know. I used to get it every time I was in London - I’d pick up some copies from Forbidden Planet, or was it in Dark They Were and Golden Eyed. And through that, I started picking up “A suivre”, “Ah ! Nana” and other French comics. And at the end of the 70s I thought about learning French, because I couldn’t understand any of these comics, I was basically just buying them for the pictures and the storytelling, so I started learning French.

So, can you speak French today?

Oui, je me débrouille… Je parle français comme une vache anglaise !

You know the expressions, that’s the hardest part surely!

(laughs)

In Luther Arkwright, but also Grandville, you feature the idea of government power controlling art, and art style and output. Clearly that’s a theme that’s quite important to you.

I think it’s about authoritarian governments controlling people, more than anything else. The nazis did it, they tried to censure what they thought was decadent and didn’t fit in with their Teutonic ideas. The Russians did the same thing. It’s the main theme in Grandville book 3, “Bête Noire”, which is inspired by the CIA and Nelson Rockefeller backing the abstract arts, because they can’t be used to represent political ideas.

So, can you speak French today?

Oui, je me débrouille… Je parle français comme une vache anglaise !

You know the expressions, that’s the hardest part surely!

(laughs)

In Luther Arkwright, but also Grandville, you feature the idea of government power controlling art, and art style and output. Clearly that’s a theme that’s quite important to you.

I think it’s about authoritarian governments controlling people, more than anything else. The nazis did it, they tried to censure what they thought was decadent and didn’t fit in with their Teutonic ideas. The Russians did the same thing. It’s the main theme in Grandville book 3, “Bête Noire”, which is inspired by the CIA and Nelson Rockefeller backing the abstract arts, because they can’t be used to represent political ideas.

One major influence I have spotted in Grandville is Sherlock Holmes, but there are many more. I even spotted Blacksad and Canardo. How do you think these up?

Sometimes I think “I’ve got to fit this character in somewhere”. Other times I’d be drawing a scene and think “oh, that character would appear naturally there”, so yeah, it depends. In the 5th book, “Force Majeure”, some of the dialogues and texts are direct references to Holmes, but the rest of them I made up.

Have you noticed that the French editions have a little summary of the various references at the end of each book?

Yes, Laurent (the publisher) has taken that from our website. After I finished the Grandville series, I thought it would be a good time to document all these things. I think it’s good to document stuff. It took me several months. I did the work with my webmaster and posted it on the website for everybody to read. And Laurent decided to use them… not all of them, but most of them.

One major influence I have spotted in Grandville is Sherlock Holmes, but there are many more. I even spotted Blacksad and Canardo. How do you think these up?

Sometimes I think “I’ve got to fit this character in somewhere”. Other times I’d be drawing a scene and think “oh, that character would appear naturally there”, so yeah, it depends. In the 5th book, “Force Majeure”, some of the dialogues and texts are direct references to Holmes, but the rest of them I made up.

Have you noticed that the French editions have a little summary of the various references at the end of each book?

Yes, Laurent (the publisher) has taken that from our website. After I finished the Grandville series, I thought it would be a good time to document all these things. I think it’s good to document stuff. It took me several months. I did the work with my webmaster and posted it on the website for everybody to read. And Laurent decided to use them… not all of them, but most of them.

The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor

You are working on a prequel to Grandville entitled “The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor”, which is another nod to Sherlock Holmes.

Yes, Stamford appears in the first novel, “A study in scarlet”. He introduces Watson to Holmes.

In “Grandville Force Majeure”, it’s the first time you hear about Lebrock’s backstory. You meet his mentor, Stamford Hawksmoor, who wears a deerstalker hat, smokes a Sherlock Holmes type pipe… he’s obviously a reference to Sherlock Holmes.

You are working on a prequel to Grandville entitled “The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor”, which is another nod to Sherlock Holmes.

Yes, Stamford appears in the first novel, “A study in scarlet”. He introduces Watson to Holmes.

In “Grandville Force Majeure”, it’s the first time you hear about Lebrock’s backstory. You meet his mentor, Stamford Hawksmoor, who wears a deerstalker hat, smokes a Sherlock Holmes type pipe… he’s obviously a reference to Sherlock Holmes.

Can you tell us a bit more about the book?

The Grandville story is set 23 years after British independence from the French empire. Well, the Hawksmoor story is set in the last dying days of the empire, leading right up to Independence Day. The events are set around that time. Of course, Hawksmoor is 23 years younger, in his 40s.

LeBrock isn’t in it. Actually, he is in one panel. In book 2 of Grandville, there was a panel where LeBrock explains that during the occupation he was in the resistance, painting slogans. And in the Hawksmoor book there is one panel where you can see LeBrock in the background painting a slogan on a wall.

But yeah, it’s all about this investigation that Hawksmoor is leading.

Can you tell us a bit more about the book?

The Grandville story is set 23 years after British independence from the French empire. Well, the Hawksmoor story is set in the last dying days of the empire, leading right up to Independence Day. The events are set around that time. Of course, Hawksmoor is 23 years younger, in his 40s.

LeBrock isn’t in it. Actually, he is in one panel. In book 2 of Grandville, there was a panel where LeBrock explains that during the occupation he was in the resistance, painting slogans. And in the Hawksmoor book there is one panel where you can see LeBrock in the background painting a slogan on a wall.

But yeah, it’s all about this investigation that Hawksmoor is leading.

Is it a similar kind of story to Grandville?

I think it’s a very different type of story, in a lot of ways. I can show you what I’ve done so far (Bryan carries on talking while I admire the pages on his tablet). I’ve done nearly 100 pages so far, out of 172 pages.

For a start, it’s not steampunk, it’s before the steam revolution. So, it’s all hansom cabs and London pea soupers. It’s very Victorian. It’s before “Nouveau”, Grandville is very “Nouveau”, but there’s no Art Nouveau in this one.

Another thing is, it’s not computer coloured, it’s water colours that are all tinted sepia, to look like Victorian photographs.

Is it a similar kind of story to Grandville?

I think it’s a very different type of story, in a lot of ways. I can show you what I’ve done so far (Bryan carries on talking while I admire the pages on his tablet). I’ve done nearly 100 pages so far, out of 172 pages.

For a start, it’s not steampunk, it’s before the steam revolution. So, it’s all hansom cabs and London pea soupers. It’s very Victorian. It’s before “Nouveau”, Grandville is very “Nouveau”, but there’s no Art Nouveau in this one.

Another thing is, it’s not computer coloured, it’s water colours that are all tinted sepia, to look like Victorian photographs.

The third big difference is that in Grandville, there’s no text boxes, it’s all spoken words, it was all in action. Whereas this is quite text heavy. Stamford Hawksmoor is narrating the whole case, in a sort of Victorian manner, which is all lettered on an old typewriter font.

The remaining difference is that the story is not as “gung ho”, it’s tinged with sadness. It’s a post-Brexit story. It’s quite a lot darker.

How long does it take you to create a page, including water colours?

About 3 days, sometimes more, it depends.

The style is completely different to your other book.

I think the art style is part of the storytelling. The art style has to really suit the type of story that you are telling. It has to reinforce the story.

The third big difference is that in Grandville, there’s no text boxes, it’s all spoken words, it was all in action. Whereas this is quite text heavy. Stamford Hawksmoor is narrating the whole case, in a sort of Victorian manner, which is all lettered on an old typewriter font.

The remaining difference is that the story is not as “gung ho”, it’s tinged with sadness. It’s a post-Brexit story. It’s quite a lot darker.

How long does it take you to create a page, including water colours?

About 3 days, sometimes more, it depends.

The style is completely different to your other book.

I think the art style is part of the storytelling. The art style has to really suit the type of story that you are telling. It has to reinforce the story.

… and since this is a Victorian story…

All the costumes are 1890s. I researched the train carriage, in fact this panel here is a reference to a Sidney Paget illustration from The Strand Magazine. It’s from “Silver Blaze”, one of the Sherlock Holmes short stories, you can see him and Watson sitting in a train compartment, facing each other.

When do you think we’ll be able to hold the book?

Hopefully next year, summer 2025, something like that. I think it’s going to take me most of this year to finish it.

I’ve read about how hard you work.

Yes, 7 days a week until 9 at night. Well, what am I gonna do, watch TV? (laughs). Every day I go for a 4-mile brisk walk.

Well, I am looking forward to next summer.

First, I think Laurent (the French publisher) is hoping to get the 5th Grandville book out in September 2024.

… and since this is a Victorian story…

All the costumes are 1890s. I researched the train carriage, in fact this panel here is a reference to a Sidney Paget illustration from The Strand Magazine. It’s from “Silver Blaze”, one of the Sherlock Holmes short stories, you can see him and Watson sitting in a train compartment, facing each other.

When do you think we’ll be able to hold the book?

Hopefully next year, summer 2025, something like that. I think it’s going to take me most of this year to finish it.

I’ve read about how hard you work.

Yes, 7 days a week until 9 at night. Well, what am I gonna do, watch TV? (laughs). Every day I go for a 4-mile brisk walk.

Well, I am looking forward to next summer.

First, I think Laurent (the French publisher) is hoping to get the 5th Grandville book out in September 2024.

Luther Arkwright

And next thing I know, I had a letter out of the blue from a guy in Edinburgh, who was publishing the British version of “Métal Hurlant”, called “Near Myths”. It was a low budget version. He asked if I could contribute a strip to that, and I said, “I’ve got this on-going strip I want to do”. And so that was how Arkwright started, in October 1978, the same month that “A contract with God” by Will Eisner was published. It ran in “Near Myths” for 5 issues – I also did work for issue 6 but it never came out.

Then, a French aristocrat called Serge Boissevain moved to London with his wife and was appalled that there was no adult comics on sale. He said, “Let’s publish one!” and he published one called “pssst!”, which lasted 12 issues. A mutual friend introduced us, and he ran the Luther Arkwright episodes that I had done already, as well as new ones. And when the “pssst!” mag finished, he published the first volume of Luther Arkwright.

And next thing I know, I had a letter out of the blue from a guy in Edinburgh, who was publishing the British version of “Métal Hurlant”, called “Near Myths”. It was a low budget version. He asked if I could contribute a strip to that, and I said, “I’ve got this on-going strip I want to do”. And so that was how Arkwright started, in October 1978, the same month that “A contract with God” by Will Eisner was published. It ran in “Near Myths” for 5 issues – I also did work for issue 6 but it never came out.

Then, a French aristocrat called Serge Boissevain moved to London with his wife and was appalled that there was no adult comics on sale. He said, “Let’s publish one!” and he published one called “pssst!”, which lasted 12 issues. A mutual friend introduced us, and he ran the Luther Arkwright episodes that I had done already, as well as new ones. And when the “pssst!” mag finished, he published the first volume of Luther Arkwright.

45 years later, how do you feel about this first story?

Some bits I really like, but there are other bits where I think, “The art is not so good, I could draw that a lot better now.” I was still learning; all that time was a massive apprenticeship, really.

You don’t write political comics as such, but there are views coming through, in both Grandville and Luther Arkwright, that feel more towards the left end of the political spectrum. Is that something you’re keen on?

Well, it’s something I am very concerned about, the rise of the right-wing all over the world, at the moment. I mean, it’s just like the nazis in the 30s, it’s frightening. The right wing is on the rise in every country in the world, including France.

Do you start writing the story thinking “I’ve got to mention these things”, or does it just happen organically?

The story comes first. I try to tell a good story. The 4th Grandville in particular, that was one of the main themes in the book, so it obviously came into it.

45 years later, how do you feel about this first story?

Some bits I really like, but there are other bits where I think, “The art is not so good, I could draw that a lot better now.” I was still learning; all that time was a massive apprenticeship, really.

You don’t write political comics as such, but there are views coming through, in both Grandville and Luther Arkwright, that feel more towards the left end of the political spectrum. Is that something you’re keen on?

Well, it’s something I am very concerned about, the rise of the right-wing all over the world, at the moment. I mean, it’s just like the nazis in the 30s, it’s frightening. The right wing is on the rise in every country in the world, including France.

Do you start writing the story thinking “I’ve got to mention these things”, or does it just happen organically?

The story comes first. I try to tell a good story. The 4th Grandville in particular, that was one of the main themes in the book, so it obviously came into it.

The last instalment of “Luther Arkwright”, "The Legend of Luther Arkwright", came out in 2022, 23 years after the previous one. What was it like revisiting these characters?

Well, it was as if I never left them, really. I created them, so I knew what they were like. It just took me a while to write a good story.

Regarding the art-style for the book…

I’ve tried to return to the original style from the first Luther Arkwright. It’s very time consuming, and it gave me a trapped nerve in my wrist, which still hasn’t gone away. Well, I’ve had therapy now, so it’s eased it quite a lot. All that cross-hatching takes for ever.

The art for the second book was very different.

I wanted to make something different from the first one. It’s a lot more “clear line”. And the format is smaller, it was commissioned by Dark Horse, I opened it to Dark Horse, and they said they’d publish it. So, it was done to American comics format. Whereas the first volume was A4… in fact the Greek edition was the same size as my artwork, so A3!

The last instalment of “Luther Arkwright”, "The Legend of Luther Arkwright", came out in 2022, 23 years after the previous one. What was it like revisiting these characters?

Well, it was as if I never left them, really. I created them, so I knew what they were like. It just took me a while to write a good story.

Regarding the art-style for the book…

I’ve tried to return to the original style from the first Luther Arkwright. It’s very time consuming, and it gave me a trapped nerve in my wrist, which still hasn’t gone away. Well, I’ve had therapy now, so it’s eased it quite a lot. All that cross-hatching takes for ever.

The art for the second book was very different.

I wanted to make something different from the first one. It’s a lot more “clear line”. And the format is smaller, it was commissioned by Dark Horse, I opened it to Dark Horse, and they said they’d publish it. So, it was done to American comics format. Whereas the first volume was A4… in fact the Greek edition was the same size as my artwork, so A3!

The Tale of One Bad Rat

On one of our trips to the Lakes, we visited Beatrix Potter’s house, you know, the children’s author. And I thought, “Well, Beatrix Potter told stories using a mix of words and pictures. It’s what I do, it’s a good connection to comics.” I started studying Beatrix Potter. I had never read Beatrix Potter, so I read all her books, and books about her - I read a dozen books about Beatrix Potter. By the time I’d finished, I thought her life wouldn’t make a very interesting story. A film came out called “Beatrix”, and they just made it interesting by making events up that didn’t happen to her.

Then one day I saw this young girl begging on Tottenham Court Road tube station, and for some reason she just put me in mind of the description of Beatrix Potter, when she was 16 - she was painfully shy. And it came from that, I thought perhaps this girl has run away from home, and she’s begging on the streets, and she has some sort of link with Beatrix Potter, some sort of synchronistic link, and it takes her to the Lake District. That was the idea of the story. Then I thought, “why has she left home? Well, her father has been abusing her.” Just like that. And I thought it was fair enough, kids leave home because they’ve been abused, and lots of them end up in London, begging on the streets. Then I started researching child sexual abuse. Mary (Bryan’s wife) got me some books out of the University library, I got some books out of the regular library, and I bought a couple of books as well. And I realised that’s what the book had to be about. It was too important to just have as a reason for her leaving home. It had to be what the whole book was about.

On one of our trips to the Lakes, we visited Beatrix Potter’s house, you know, the children’s author. And I thought, “Well, Beatrix Potter told stories using a mix of words and pictures. It’s what I do, it’s a good connection to comics.” I started studying Beatrix Potter. I had never read Beatrix Potter, so I read all her books, and books about her - I read a dozen books about Beatrix Potter. By the time I’d finished, I thought her life wouldn’t make a very interesting story. A film came out called “Beatrix”, and they just made it interesting by making events up that didn’t happen to her.

Then one day I saw this young girl begging on Tottenham Court Road tube station, and for some reason she just put me in mind of the description of Beatrix Potter, when she was 16 - she was painfully shy. And it came from that, I thought perhaps this girl has run away from home, and she’s begging on the streets, and she has some sort of link with Beatrix Potter, some sort of synchronistic link, and it takes her to the Lake District. That was the idea of the story. Then I thought, “why has she left home? Well, her father has been abusing her.” Just like that. And I thought it was fair enough, kids leave home because they’ve been abused, and lots of them end up in London, begging on the streets. Then I started researching child sexual abuse. Mary (Bryan’s wife) got me some books out of the University library, I got some books out of the regular library, and I bought a couple of books as well. And I realised that’s what the book had to be about. It was too important to just have as a reason for her leaving home. It had to be what the whole book was about.

Is it true that “The tale of one bad rat” is used in schools and sex abuse centres?

Yes, in several countries. The book has been published in about 18 countries, something like that, I lost count. It’s just come out again in Italy last year, it’s its fourth publisher there. But yeah, I do signings in different countries, and I’ve been told that they used it many times in the centres to get the kids to talk about their own problems. They read and talk about Helen, and it helps them to talk about their own problems.

I believe everyone in the book was modelled on a real person.

Not the characters themselves. I wrote the characters, then cast the story. I looked for people who looked like what I thought the characters would look like. You know, I usually make things up, but I wanted this one to be quite realistic, because it’s about a serious issue. So, I took some photographs and drew it from the photographs, which is what François Bourgeon does. Frank Hampson used to do it in Dan Dare as well. And I thought “well that’s a way to do it”.

Is it true that “The tale of one bad rat” is used in schools and sex abuse centres?

Yes, in several countries. The book has been published in about 18 countries, something like that, I lost count. It’s just come out again in Italy last year, it’s its fourth publisher there. But yeah, I do signings in different countries, and I’ve been told that they used it many times in the centres to get the kids to talk about their own problems. They read and talk about Helen, and it helps them to talk about their own problems.

I believe everyone in the book was modelled on a real person.

Not the characters themselves. I wrote the characters, then cast the story. I looked for people who looked like what I thought the characters would look like. You know, I usually make things up, but I wanted this one to be quite realistic, because it’s about a serious issue. So, I took some photographs and drew it from the photographs, which is what François Bourgeon does. Frank Hampson used to do it in Dan Dare as well. And I thought “well that’s a way to do it”.

There’s one character, the innkeeper, he was actually based on a friend of ours at the time. That was his character, he was like that. But he was the only one, the rest of them were cast.

Did you draw the locations (London, the Lakes) from photos? From memory? Or did you go there?

All the locations in “Bad rat” are based on real places. I happened to be in London, I had obligations there, so I took snaps, and drew from them. And the Lake District ones as well.

Beatrix Potter used to paint from life, and she said she used to adapt and improve the scenery, to make it better in the illustrations. I did that with Cat Bells, that view of Cat Bells walking up it, if you actually looked at a picture of it, from that point, it doesn’t look as steep as how I drew it! (see page to the right, and this photo for reference - source : walkmyworld.com)

Bryan, thank you for your time.

You’re welcome.

There’s one character, the innkeeper, he was actually based on a friend of ours at the time. That was his character, he was like that. But he was the only one, the rest of them were cast.

Did you draw the locations (London, the Lakes) from photos? From memory? Or did you go there?

All the locations in “Bad rat” are based on real places. I happened to be in London, I had obligations there, so I took snaps, and drew from them. And the Lake District ones as well.

Beatrix Potter used to paint from life, and she said she used to adapt and improve the scenery, to make it better in the illustrations. I did that with Cat Bells, that view of Cat Bells walking up it, if you actually looked at a picture of it, from that point, it doesn’t look as steep as how I drew it! (see page to the right, and this photo for reference - source : walkmyworld.com)

Bryan, thank you for your time.

You’re welcome.Site réalisé avec CodeIgniter, jQuery, Bootstrap, fancyBox, Open Iconic, typeahead.js, Google Charts, Google Maps, echo

Copyright © 2001 - 2026 BDTheque | Contact | Les cookies sur le site | Les stats du site